6 Spin as a statistical degree of freedom

Spin is generally believed to be a phenomenon of quantum-theoretic origin. For a long period of time,

following Dirac’s derivation of his relativistic equation, it was also believed to be essentially of

relativistic origin. This has changed since the work of [60], [41], [5], [19], [54] and others, who

showed that spin may be derived entirely in the framework of non-relativistic QT without using

any relativistic concepts. Thus, a new derivation of non-relativistic QT like the present one should

also include a derivation of the phenomenon of spin. This will be done in this and the next two

sections.

A simple idea to extend the present theory is to assume that sometimes - under certain external conditions to be

identified later - a situation occurs where the behavior of our statistical ensemble of particles cannot longer be

described by  alone but requires, e.g., the double number of field variables; let us denote these by

alone but requires, e.g., the double number of field variables; let us denote these by

(we restrict ourselves here to spin one-half). The relations defining this

generalized theory should be formulated in such a way that the previous relations are obtained in the

appropriate limits. One could say that we undertake an attempt to introduce a new (discrete) degree of

freedom for the ensemble. If we are able to derive a non-trivial set of differential equations - with

coupling between

(we restrict ourselves here to spin one-half). The relations defining this

generalized theory should be formulated in such a way that the previous relations are obtained in the

appropriate limits. One could say that we undertake an attempt to introduce a new (discrete) degree of

freedom for the ensemble. If we are able to derive a non-trivial set of differential equations - with

coupling between  and

and  - then such a degree of freedom could exist in

nature.

- then such a degree of freedom could exist in

nature.

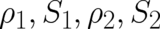

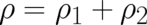

Using these guidelines, the basic equations of the generalized theory can be easily formulated. The probability

density and probability current take the form  and

and  , with

, with

(

( ) defined in terms of

) defined in terms of  exactly as before (see section 2). Then, the continuity

equation is given by

exactly as before (see section 2). Then, the continuity

equation is given by

| (56) |

where we took the possibility of multi-valuedness of the “phases“ already into account, as indicated by the

notation  . The statistical conditions are given by the two relations

. The statistical conditions are given by the two relations

which are similar to the relations used previously (in section 2 and in I), and by an additional

equation

| (59) |

which is required as a consequence of our larger number of dynamic variables. Eq. (59) is best explained later; it

is written down here for completeness. The forces  and

and  on the

r.h.s. of (58) and (59) are again subject to the “statistical constraint“, which has been defined in section 3. The

expectation values are defined as in (9)-(11).

on the

r.h.s. of (58) and (59) are again subject to the “statistical constraint“, which has been defined in section 3. The

expectation values are defined as in (9)-(11).

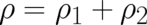

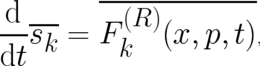

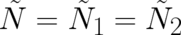

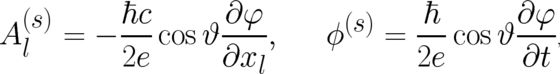

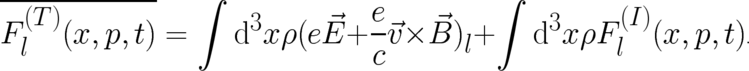

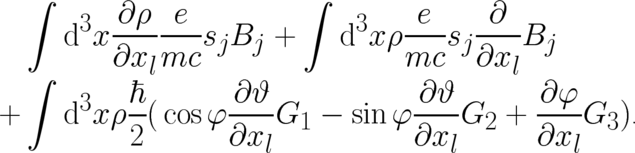

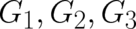

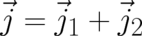

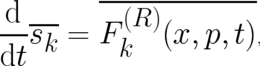

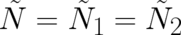

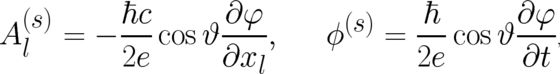

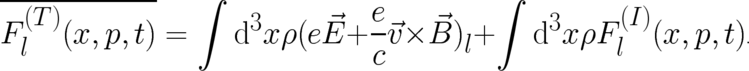

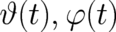

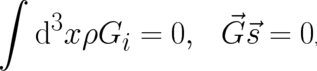

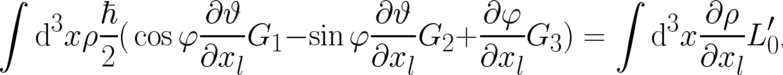

Performing mathematical manipulations similar to the ones reported in section 2, the l.h.s. of Eq. (58) takes the

form

![∫

˜ ˜

-d------ 3 ∂--ρ1- ∂-S1--- ∂-ρ2--∂--S2--

pk = d x [ +

dt ∂ t ∂ xk ∂ t ∂ xk

∂ ρ ∂ ˜S ∂ ρ ∂ S˜

- ----1------1- - ----2------2--+ ρ S˜ (1 ) + ρ ˜S (2 ) ],

1 [j,k ] 2 [j,k ]

∂ xk ∂ t ∂ xk ∂ t](stader277x.png) | (60) |

where the quantities ![˜ (i )

S , i = 1, 2

[j,k ]](stader278x.png) are defined as above [see Eq. (6)] but with

are defined as above [see Eq. (6)] but with  replaced by

replaced by

.

.

Let us write now  in analogy to section 2 in the form

in analogy to section 2 in the form  , as a sum of a

single-valued part

, as a sum of a

single-valued part  and a multi-valued part

and a multi-valued part  . If

. If  and

and  are to represent an external

influence, they must be identical and a single multi-valued part

are to represent an external

influence, they must be identical and a single multi-valued part  may be used

instead. The derivatives of

may be used

instead. The derivatives of  with respect to

with respect to  and

and  must be single-valued and we may

write

must be single-valued and we may

write

| (61) |

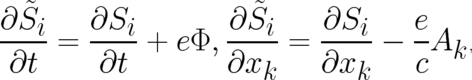

using the same familiar electrodynamic notation as in section 2. In this way we arrive at eight single-valued

functions to describe the external conditions and the dynamical state of our system, namely  and

and

.

.

In a next step we replace  by new dynamic variables

by new dynamic variables  defined by

defined by

| (62) |

A transformation similar to Eq. (62) has been introduced by [65] in his reformulation of Pauli’s equation.

Obviously, the variables  describe ’center of mass’ properties (which are common to both states

describe ’center of mass’ properties (which are common to both states  and

and

) while

) while  describe relative (internal) properties of the system.

describe relative (internal) properties of the system.

The dynamical variables  and

and  are not decoupled from each other. It turns out (see below)

that the influence of

are not decoupled from each other. It turns out (see below)

that the influence of  on

on  can be described in a (formally) similar way as the influence of an

external electromagnetic field if a ’vector potential’

can be described in a (formally) similar way as the influence of an

external electromagnetic field if a ’vector potential’  and a ’scalar potential’

and a ’scalar potential’  , defined

by

, defined

by

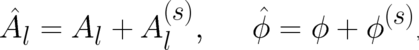

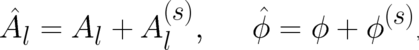

| (63) |

are introduced. Denoting these fields as ’potentials’, we should bear in mind that they are not externally

controlled but defined in terms of the internal dynamical variables. Using the abbreviations

| (64) |

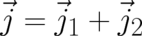

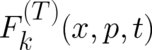

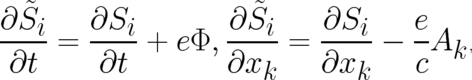

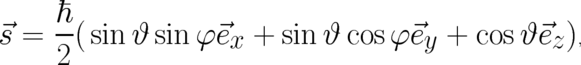

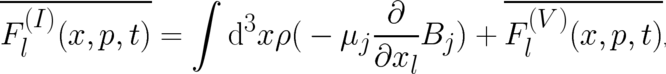

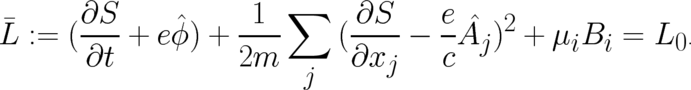

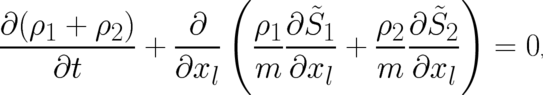

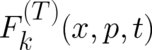

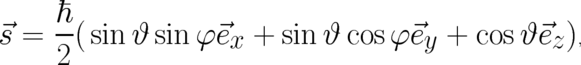

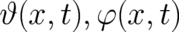

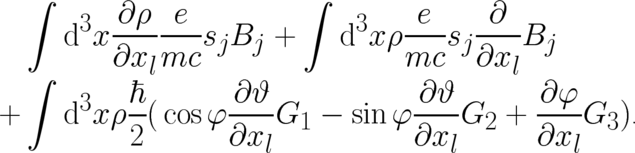

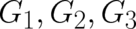

the second statistical condition (58) can be written in the following compact form

![∫ ∑

3 ∂ ρ ∂ S 1 ∂ S e 2

- d x -----[( ----- + e ˆϕ ) + ------ (-------- --Aˆj ) ]

∂ x ∂ t 2m ∂ x c

l j j

∫ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ

3 e- ∂--Al-- ∂-Aj--- e- ∂-Al--- -∂-ϕ--

+ d x ρ [ - vj ( - ) - - e ]

c ∂ xj ∂ x c ∂ t ∂ x

-------------------- ∫ l l

= F (T )(x, p, t) = d3x ρF (T )(x, p, t ),

l l](stader309x.png) | (65) |

which shows a formal similarity to the spinless case [see (14) and (24)]. The components of the velocity field

in (65) are given by

| (66) |

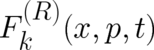

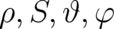

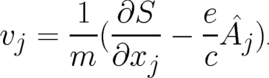

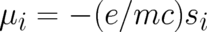

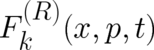

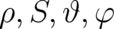

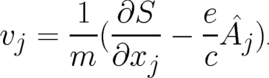

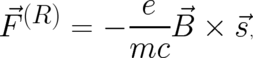

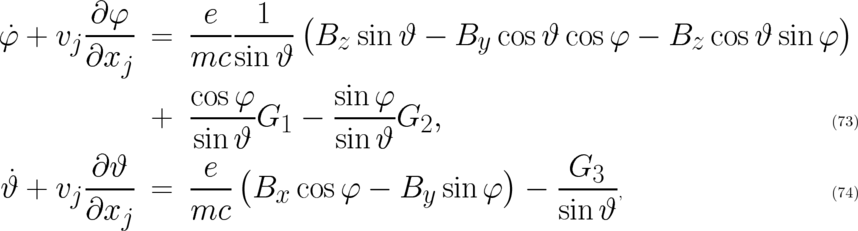

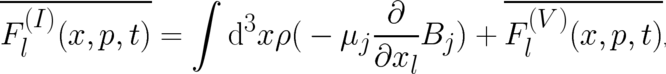

If now fields  and

and  are introduced by relations analogous to (23), the second

line of (65) may be written in the form

are introduced by relations analogous to (23), the second

line of (65) may be written in the form

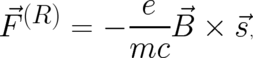

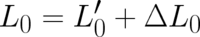

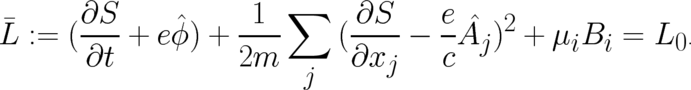

![∫

e e

d3x ρ [(e E⃗ + --⃗v × B⃗ ) + (e E ⃗(s) + --⃗v × B ⃗(s )) ],

l l

c c](stader313x.png) | (67) |

which shows that both types of fields, the external fields as well as the internal fields due to  , enter the

theory in the same way, namely in the form of a Lorentz force.

, enter the

theory in the same way, namely in the form of a Lorentz force.

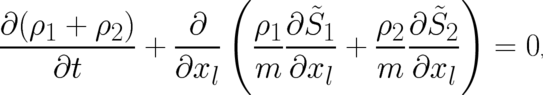

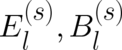

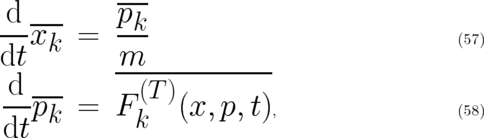

The first, externally controlled Lorentz force in (67) may be eliminated in exactly the same manner as in

section 3 by writing

| (68) |

This means that one of the forces acting on the system as a whole is again given by a Lorentz force; there

may be other nontrivial forces  which are still to be determined. The second ’internal’

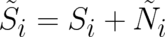

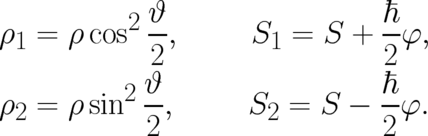

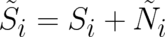

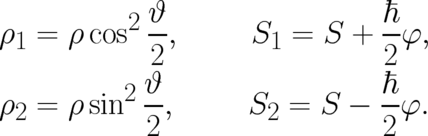

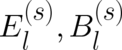

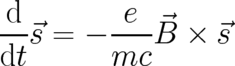

Lorentz force in (67) can, of course, not be eliminated in this way. In order to proceed, the third

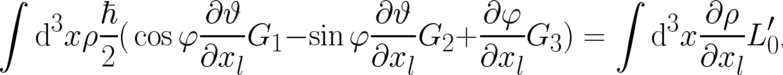

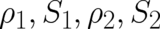

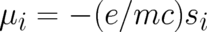

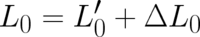

statistical condition (59) must be implemented. To do that it is useful to rewrite Eq. (65) in the

form

which are still to be determined. The second ’internal’

Lorentz force in (67) can, of course, not be eliminated in this way. In order to proceed, the third

statistical condition (59) must be implemented. To do that it is useful to rewrite Eq. (65) in the

form

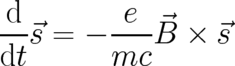

![∫

∂ ρ ∂ S 1 ∑ ∂ S e

3 ------ ----- ˆ ------ ------- -- ˆ 2

- d x [( + e ϕ ) + ( - Aj ) ]

∂ xl ∂ t 2m ∂ xj c

j

∫

3 ℏ-- -∂-ϑ-- ∂-φ-- -∂-φ--- ∂-φ--- ∂-ϑ-- -∂-ϑ---

+ d x ρ sin ϑ ( [ + vj ] - [ + vj ])

2 ∂ xl ∂ t ∂ xj ∂ xl ∂ t ∂ xj

------------------- ∫

(I ) (I )

= F (x, p, t) = d3x ρF (x, p, t ),

l l](stader317x.png) | (69) |

using (67), (68) and the definition (63) of the fields  and

and  .

.

We interpret the fields  and

and  as angles (with

as angles (with  measured from the

measured from the  axis of our coordinate

system) determining the direction of a vector

axis of our coordinate

system) determining the direction of a vector

| (70) |

of constant length  . As a consequence,

. As a consequence,  and

and  are perpendicular to each other and the classical force

are perpendicular to each other and the classical force

in Eq. (59) should be of the form

in Eq. (59) should be of the form  , where

, where  is an unknown field. In

contrast to the ’external force’, we are unable to determine the complete form of this ’internal’

force from the statistical constraint [an alternative treatment will be reported in section 8] and

set

is an unknown field. In

contrast to the ’external force’, we are unable to determine the complete form of this ’internal’

force from the statistical constraint [an alternative treatment will be reported in section 8] and

set

| (71) |

where  is the external ’magnetic field’, as defined by Eq. (23), and the factor in front of

is the external ’magnetic field’, as defined by Eq. (23), and the factor in front of  has been

chosen to yield the correct

has been

chosen to yield the correct  factor of the electron.

factor of the electron.

The differential equation

| (72) |

for particle variables  describes the rotational state of a classical magnetic dipole in a

magnetic field, see [60]. Recall that we do not require that (72) is fulfilled in the present theory. The present

variables are the fields

describes the rotational state of a classical magnetic dipole in a

magnetic field, see [60]. Recall that we do not require that (72) is fulfilled in the present theory. The present

variables are the fields  which may be thought of as describing a kind of

’rotational state’ of the statistical ensemble as a whole, and have to fulfill the ’averaged version’ (59)

of (72).

which may be thought of as describing a kind of

’rotational state’ of the statistical ensemble as a whole, and have to fulfill the ’averaged version’ (59)

of (72).

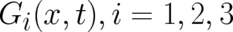

Performing steps similar to the ones described in I (see also section 2), the third statistical condition (59)

implies the following differential relations,

for the dynamic variables  and

and  . These equations contain three fields

. These equations contain three fields  which have to obey the conditions

which have to obey the conditions

| (75) |

and are otherwise arbitrary. The ’total derivatives’ of  and

and  in (69) may now be eliminated with the

help of (73),(74) and the second line of Eq. (69) takes the form

in (69) may now be eliminated with the

help of (73),(74) and the second line of Eq. (69) takes the form

| (76) |

The second term in (76) presents an external macroscopic force. It may be eliminated from (69) by

writing

| (77) |

where the magnetic moment of the electron  has been introduced. The

first term on the r.h.s. of (77) is the expectation value of the well-known electrodynamical force

exerted by an inhomogeneous magnetic field on the translational motion of a magnetic dipole; this

classical force plays an important role in the standard interpretation of the quantum-mechanical

Stern-Gerlach effect. It is satisfying that both translational forces, the Lorentz force as well as this dipole

force, can be derived in the present approach. The remaining unknown force

has been introduced. The

first term on the r.h.s. of (77) is the expectation value of the well-known electrodynamical force

exerted by an inhomogeneous magnetic field on the translational motion of a magnetic dipole; this

classical force plays an important role in the standard interpretation of the quantum-mechanical

Stern-Gerlach effect. It is satisfying that both translational forces, the Lorentz force as well as this dipole

force, can be derived in the present approach. The remaining unknown force  in (77)

leads (in the same way as in section 3) to a mechanical potential

in (77)

leads (in the same way as in section 3) to a mechanical potential  , which will be omitted for

brevity.

, which will be omitted for

brevity.

The integrand of the first term in (76) is linear in the derivative of  with respect to

with respect to  . It may

consequently be added to the first line of (69) which has the same structure. Therefore, it represents (see below)

a contribution to the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi differential equation. The third term in (76) has the

mathematical structure of a force term, but does not contain any externally controlled fields. Thus, it must also

represent a contribution to the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi equation. This implies that this third term can be

written as

. It may

consequently be added to the first line of (69) which has the same structure. Therefore, it represents (see below)

a contribution to the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi differential equation. The third term in (76) has the

mathematical structure of a force term, but does not contain any externally controlled fields. Thus, it must also

represent a contribution to the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi equation. This implies that this third term can be

written as

| (78) |

where  is an unknown field depending on

is an unknown field depending on  .

.

Collecting terms and restricting ourselves, as in section 5, to an isotropic law, the statistical condition (69)

takes the form of a generalized Hamilton-Jacobi equation:

| (79) |

The unknown function  must contain

must contain  but may also contain other terms, let us write

but may also contain other terms, let us write

.

.

alone but requires, e.g., the double number of field variables; let us denote these by

alone but requires, e.g., the double number of field variables; let us denote these by

(we restrict ourselves here to spin one-half). The relations defining this

generalized theory should be formulated in such a way that the previous relations are obtained in the

appropriate limits. One could say that we undertake an attempt to introduce a new (discrete) degree of

freedom for the ensemble. If we are able to derive a non-trivial set of differential equations - with

coupling between

(we restrict ourselves here to spin one-half). The relations defining this

generalized theory should be formulated in such a way that the previous relations are obtained in the

appropriate limits. One could say that we undertake an attempt to introduce a new (discrete) degree of

freedom for the ensemble. If we are able to derive a non-trivial set of differential equations - with

coupling between  and

and  - then such a degree of freedom could exist in

nature.

- then such a degree of freedom could exist in

nature.

and

and  , with

, with

(

( ) defined in terms of

) defined in terms of  exactly as before (see section

exactly as before (see section

. The statistical conditions are given by the two relations

. The statistical conditions are given by the two relations

and

and  on the

r.h.s. of (

on the

r.h.s. of (![∫

˜ ˜

-d------ 3 ∂--ρ1- ∂-S1--- ∂-ρ2--∂--S2--

pk = d x [ +

dt ∂ t ∂ xk ∂ t ∂ xk

∂ ρ ∂ ˜S ∂ ρ ∂ S˜

- ----1------1- - ----2------2--+ ρ S˜ (1 ) + ρ ˜S (2 ) ],

1 [j,k ] 2 [j,k ]

∂ xk ∂ t ∂ xk ∂ t](stader277x.png)

![˜ (i )

S , i = 1, 2

[j,k ]](stader278x.png) are defined as above [see Eq. (

are defined as above [see Eq. ( replaced by

replaced by

.

.

in analogy to section

in analogy to section  , as a sum of a

single-valued part

, as a sum of a

single-valued part  and a multi-valued part

and a multi-valued part  . If

. If  and

and  are to represent an external

influence, they must be identical and a single multi-valued part

are to represent an external

influence, they must be identical and a single multi-valued part  may be used

instead. The derivatives of

may be used

instead. The derivatives of  with respect to

with respect to  and

and  must be single-valued and we may

write

must be single-valued and we may

write

and

and

.

.

by new dynamic variables

by new dynamic variables  defined by

defined by

describe ’center of mass’ properties (which are common to both states

describe ’center of mass’ properties (which are common to both states  and

and

) while

) while  describe relative (internal) properties of the system.

describe relative (internal) properties of the system.

and

and  are not decoupled from each other. It turns out (see below)

that the influence of

are not decoupled from each other. It turns out (see below)

that the influence of  on

on  can be described in a (formally) similar way as the influence of an

external electromagnetic field if a ’vector potential’

can be described in a (formally) similar way as the influence of an

external electromagnetic field if a ’vector potential’  and a ’scalar potential’

and a ’scalar potential’  , defined

by

, defined

by

![∫ ∑

3 ∂ ρ ∂ S 1 ∂ S e 2

- d x -----[( ----- + e ˆϕ ) + ------ (-------- --Aˆj ) ]

∂ x ∂ t 2m ∂ x c

l j j

∫ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ

3 e- ∂--Al-- ∂-Aj--- e- ∂-Al--- -∂-ϕ--

+ d x ρ [ - vj ( - ) - - e ]

c ∂ xj ∂ x c ∂ t ∂ x

-------------------- ∫ l l

= F (T )(x, p, t) = d3x ρF (T )(x, p, t ),

l l](stader309x.png)

and

and  are introduced by relations analogous to (

are introduced by relations analogous to (![∫

e e

d3x ρ [(e E⃗ + --⃗v × B⃗ ) + (e E ⃗(s) + --⃗v × B ⃗(s )) ],

l l

c c](stader313x.png)

, enter the

theory in the same way, namely in the form of a Lorentz force.

, enter the

theory in the same way, namely in the form of a Lorentz force.

which are still to be determined. The second ’internal’

Lorentz force in (

which are still to be determined. The second ’internal’

Lorentz force in (![∫

∂ ρ ∂ S 1 ∑ ∂ S e

3 ------ ----- ˆ ------ ------- -- ˆ 2

- d x [( + e ϕ ) + ( - Aj ) ]

∂ xl ∂ t 2m ∂ xj c

j

∫

3 ℏ-- -∂-ϑ-- ∂-φ-- -∂-φ--- ∂-φ--- ∂-ϑ-- -∂-ϑ---

+ d x ρ sin ϑ ( [ + vj ] - [ + vj ])

2 ∂ xl ∂ t ∂ xj ∂ xl ∂ t ∂ xj

------------------- ∫

(I ) (I )

= F (x, p, t) = d3x ρF (x, p, t ),

l l](stader317x.png)

and

and  .

.

and

and  as angles (with

as angles (with  measured from the

measured from the  axis of our coordinate

system) determining the direction of a vector

axis of our coordinate

system) determining the direction of a vector

. As a consequence,

. As a consequence,  and

and  are perpendicular to each other and the classical force

are perpendicular to each other and the classical force

in Eq. (

in Eq. ( , where

, where  is an unknown field. In

contrast to the ’external force’, we are unable to determine the complete form of this ’internal’

force from the statistical constraint [an alternative treatment will be reported in section

is an unknown field. In

contrast to the ’external force’, we are unable to determine the complete form of this ’internal’

force from the statistical constraint [an alternative treatment will be reported in section

is the external ’magnetic field’, as defined by Eq. (

is the external ’magnetic field’, as defined by Eq. ( has been

chosen to yield the correct

has been

chosen to yield the correct  factor of the electron.

factor of the electron.

describes the rotational state of a classical magnetic dipole in a

magnetic field, see

describes the rotational state of a classical magnetic dipole in a

magnetic field, see  which may be thought of as describing a kind of

’rotational state’ of the statistical ensemble as a whole, and have to fulfill the ’averaged version’ (

which may be thought of as describing a kind of

’rotational state’ of the statistical ensemble as a whole, and have to fulfill the ’averaged version’ (

and

and  . These equations contain three fields

. These equations contain three fields  which have to obey the conditions

which have to obey the conditions

and

and  in (

in (

has been introduced. The

first term on the r.h.s. of (

has been introduced. The

first term on the r.h.s. of ( in (

in ( , which will be omitted for

brevity.

, which will be omitted for

brevity.

with respect to

with respect to  . It may

consequently be added to the first line of (

. It may

consequently be added to the first line of (

is an unknown field depending on

is an unknown field depending on  .

.

must contain

must contain  but may also contain other terms, let us write

but may also contain other terms, let us write

.

.