. The first of these is the continuity equation (64), which is

given, in terms of the present variables, by

. The first of these is the continuity equation (64), which is

given, in terms of the present variables, by

Let us summarize at this point what has been achieved so far. We have four coupled differential equations for

our dynamic field variables  . The first of these is the continuity equation (64), which is

given, in terms of the present variables, by

. The first of these is the continuity equation (64), which is

given, in terms of the present variables, by

![[ ]

∂ ρ ∂ ρ ( ∂ S e )

----- ------ ---- ------- -- ˆ

+ - Aj = 0.

∂ t ∂ xl m ∂ xj c](soq3dweb374x.png) | (88) |

The three other differential equations, the evolution equations (81), (82) and the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi

equation (87), do not yet possess a definite mathematical form. They contain four unknown functions

which are constrained, but not determined, by (83), (86).

which are constrained, but not determined, by (83), (86).

The simplest choice, from a formal point of view, is  . In this limit the present

theory agrees with Schiller’s field-theoretic (Hamilton-Jacobi) version [31] of the equations of motion of a

classical dipole. This is a classical (statistical) theory despite the fact that it contains [see (71)] a number

. In this limit the present

theory agrees with Schiller’s field-theoretic (Hamilton-Jacobi) version [31] of the equations of motion of a

classical dipole. This is a classical (statistical) theory despite the fact that it contains [see (71)] a number  .

But this classical theory is not realized in nature; at least not in the microscopic domain. The reason is that the

simplest choice from a formal point of view is not the simplest choice from a physical point of view. The

postulate of maximal simplicity (Ockham’s razor) implies equal probabilities and the principle of maximal

entropy in classical statistical physics. A similar principle which is able to ’explain’ the nonexistence of

classical physics (in the microscopic domain) is the principle of minimal Fisher information [11]. The

relation between the two (classical and quantum-mechanical) principles has been discussed in detail in

I.

.

But this classical theory is not realized in nature; at least not in the microscopic domain. The reason is that the

simplest choice from a formal point of view is not the simplest choice from a physical point of view. The

postulate of maximal simplicity (Ockham’s razor) implies equal probabilities and the principle of maximal

entropy in classical statistical physics. A similar principle which is able to ’explain’ the nonexistence of

classical physics (in the microscopic domain) is the principle of minimal Fisher information [11]. The

relation between the two (classical and quantum-mechanical) principles has been discussed in detail in

I.

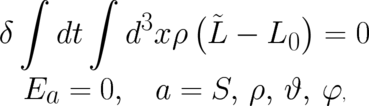

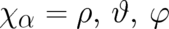

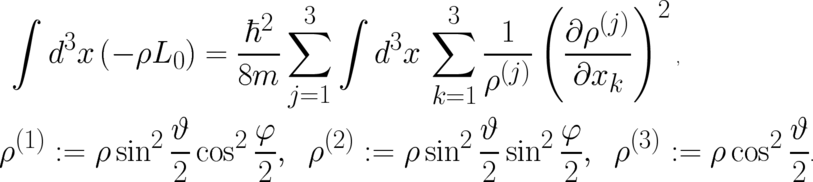

The mathematical formulation of the principle of minimal Fisher information for the present problem

requires a generalization, as compared to I, because we have now several fields with coupled time-evolution

equations. As a consequence, the spatial integral (spatial average) over  in the variational

problem (52) should be replaced by a space-time integral, and the variation should be performed with respect to

all four variables. The problem can be written in the form

in the variational

problem (52) should be replaced by a space-time integral, and the variation should be performed with respect to

all four variables. The problem can be written in the form

| (89) (90) |

is a shorthand notation for the equations (88), (87), (82) (81). Eqs. (89), (90)

require that the four Euler-Lagrange equations of the variational problem (89) agree with the differential

equations (90). This imposes conditions for the unknown functions

is a shorthand notation for the equations (88), (87), (82) (81). Eqs. (89), (90)

require that the four Euler-Lagrange equations of the variational problem (89) agree with the differential

equations (90). This imposes conditions for the unknown functions  . If the solutions of (89), (90)

for

. If the solutions of (89), (90)

for  are inserted in the variational problem (89), the four relations (90) become redundant and

are inserted in the variational problem (89), the four relations (90) become redundant and

becomes the Lagrangian density of our problem. Thus, Eqs. (89) and (90) represent a

method to construct a Lagrangian.

becomes the Lagrangian density of our problem. Thus, Eqs. (89) and (90) represent a

method to construct a Lagrangian.

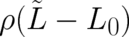

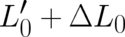

We assume a functional form  , where

, where  .

This means

.

This means  does not possess an explicit

does not possess an explicit  -dependence and does not depend on

-dependence and does not depend on  (this would

lead to a modification of the continuity equation). We further assume that

(this would

lead to a modification of the continuity equation). We further assume that  does not depend on

time-derivatives of

does not depend on

time-derivatives of  (the basic structure of the time-evolution equations should not be affected) and on

spatial derivatives higher than second order. These second order derivatives must be taken into account but

should not give contributions to the variational equations (a more detailed discussion of the last point has been

given in I).

(the basic structure of the time-evolution equations should not be affected) and on

spatial derivatives higher than second order. These second order derivatives must be taken into account but

should not give contributions to the variational equations (a more detailed discussion of the last point has been

given in I).

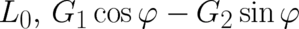

The variation with respect to  reproduces the continuity equation which is unimportant for the

determination of

reproduces the continuity equation which is unimportant for the

determination of  . Performing the variation with respect to

. Performing the variation with respect to  and taking the

corresponding conditions (87), (82) (81) into account leads to the following differential equations for

and taking the

corresponding conditions (87), (82) (81) into account leads to the following differential equations for

and

and  ,

,

| (91) (92) (93) |

does not occur in (91)-(93) in agreement with our assumptions about the form of

does not occur in (91)-(93) in agreement with our assumptions about the form of

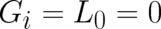

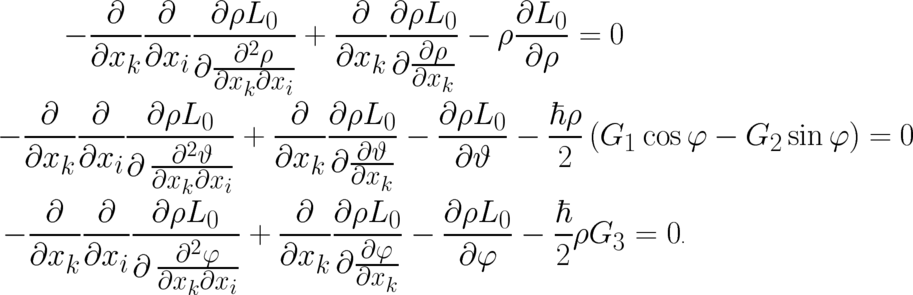

. It is easy to see that a proper solution (with vanishing variational contributions from the second order

derivatives) of (91)-(93) is given by

. It is easy to see that a proper solution (with vanishing variational contributions from the second order

derivatives) of (91)-(93) is given by ![[ ( ) ( ) ]

ℏ2 1 ∂ ∂ √ -- 1 ∂ φ 2 1 ∂ ϑ 2

------ ---------------- -- 2 ----- -- -----

L0 = √ -- ρ - sin ϑ -

2m ρ ∂ ⃗x ∂ ⃗x 4 ∂ ⃗x 4 ∂ ⃗x

[ ( ) ]

ℏ2 1 ∂ φ 2 1 ∂ ∂ ϑ

------ -- ----- -- ----- -----

ℏG1 cos φ - ℏG2 sin φ = sin 2 ϑ - ρ

2m 2 ∂ ⃗x ρ ∂ ⃗x ∂ ⃗x

2

ℏ 1 ∂ ( 2 ∂ φ )

ℏG = - ------- ----- ρ sin ϑ ----- .

3 2m ρ ∂ ⃗x ∂ ⃗x](soq3dweb399x.png) | (94) (95) (96) |

, where

, where  is again Planck’s constant. This second

is again Planck’s constant. This second  is related to the quantum-mechanical

principle of maximal disorder. It is in the present approach not related in any obvious way to the previous

“classical“

is related to the quantum-mechanical

principle of maximal disorder. It is in the present approach not related in any obvious way to the previous

“classical“  which denotes the amplitude of a rotation.

which denotes the amplitude of a rotation.

The solutions for  may be obtained with the help of the second condition (

may be obtained with the help of the second condition ( )

listed in Eq. (83). The result may be written in the form

)

listed in Eq. (83). The result may be written in the form

| (97) |

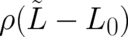

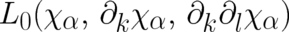

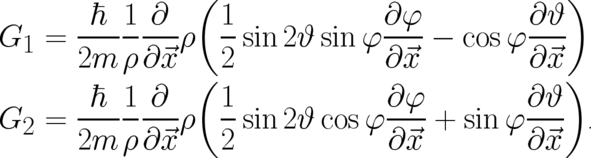

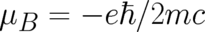

Eqs. (96) and (97) show that the first condition listed in (83) is also satisfied. The last condition is also fulfilled:

can be written as

can be written as  , where

, where

![[ ( ) ( ) ]

ℏ2 ∂ φ 2 ∂ ϑ 2 ℏ2 1 ∂ ∂ √ --

′ ------ 2 ----- ----- ---------------------

L 0 = - sin ϑ - , ΔL0 = √ -- ρ,

8m ∂ ⃗x ∂ ⃗x 2m ρ ∂ ⃗x ∂ ⃗x](soq3dweb409x.png) | (98) |

and  fulfills (86). We see that

fulfills (86). We see that  is a quantum-mechanical contribution to the rotational motion

while

is a quantum-mechanical contribution to the rotational motion

while  is related to the probability density of the ensemble (as could have been guessed

considering the mathematical form of these terms). The last term is the same as in the spinless case

[see (59)].

is related to the probability density of the ensemble (as could have been guessed

considering the mathematical form of these terms). The last term is the same as in the spinless case

[see (59)].

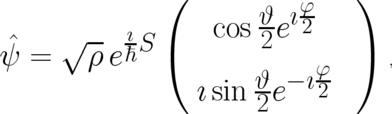

The remaining task is to show that the above solution for  does indeed lead to a (appropriately

generalized) Fisher functional. This can be done in several ways. The simplest is to use the following result due

to Reginatto [28]:

does indeed lead to a (appropriately

generalized) Fisher functional. This can be done in several ways. The simplest is to use the following result due

to Reginatto [28]:

| (99) (100) |

represent the probability that a particle is at space-time point

represent the probability that a particle is at space-time point  and

and

points into direction

points into direction  . Inserting (94) the validity of (99) may easily be verified. The r.h.s. of Eq. (99)

shows that the averaged value of

. Inserting (94) the validity of (99) may easily be verified. The r.h.s. of Eq. (99)

shows that the averaged value of  represents indeed a Fisher functional, which completes our calculation of

the ’quantum terms’

represents indeed a Fisher functional, which completes our calculation of

the ’quantum terms’  .

.

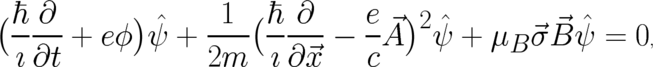

Summarizing, our assumption, that under certain external conditions four state variables instead of two may

be required, led to a nontrivial result, namely the four coupled differential equations (88), (87), (82) (81) with

given by (94), (97), (96). The external condition which stimulates this splitting is

given by a gauge field; the most important case is a magnetic field

given by (94), (97), (96). The external condition which stimulates this splitting is

given by a gauge field; the most important case is a magnetic field  but other possibilities do

exist (see below). These four differential equations are equivalent to the much simpler differential

equation

but other possibilities do

exist (see below). These four differential equations are equivalent to the much simpler differential

equation

| (101) |

which is linear in the complex-valued two-component state variable  and is referred to as Pauli equation (the

components of the vector

and is referred to as Pauli equation (the

components of the vector  are the three Pauli matrices and

are the three Pauli matrices and  ). To see the

equivalence one writes [34],[14]

). To see the

equivalence one writes [34],[14]

| (102) |

and evaluates the real and imaginary parts of the two scalar equations (101). This leads to the four differential equations (88), (87), (82) (81) and completes the present spin theory.

In terms of the real-valued functions  the quantum-mechanical solutions (94),(96),(97)

for

the quantum-mechanical solutions (94),(96),(97)

for  look complicated in comparison to the classical solutions

look complicated in comparison to the classical solutions  . In

terms of the variable

. In

terms of the variable  the situation changes to the contrary: The quantum-mechanical equation

becomes simple (linear) and the classical equation, which has been derived by Schiller [31], becomes

complicated (nonlinear). It is satisfying that the simplicity of the underlying physical principle

(principle of maximal disorder) leads to a simple mathematical representation of the final basic

equation.

the situation changes to the contrary: The quantum-mechanical equation

becomes simple (linear) and the classical equation, which has been derived by Schiller [31], becomes

complicated (nonlinear). It is satisfying that the simplicity of the underlying physical principle

(principle of maximal disorder) leads to a simple mathematical representation of the final basic

equation.

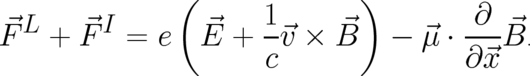

Besides the Pauli equation we found, as a second important result of our spin calculation, that the following local force is compatible with the statistical constraint:

| (103) |

Here, the velocity field  [see (34),(35)] and the magnetic moment field

[see (34),(35)] and the magnetic moment field

[see (78),(85)] have been replaced by corresponding particle

quantities

[see (78),(85)] have been replaced by corresponding particle

quantities  and

and  ; the dot denotes the inner product between

; the dot denotes the inner product between  and

and  . The first of the

two forces in (103) is the Lorentz force; it has been derived here (basically in the same manner as in the spinless

case) from first principles without any additional assumptions. The same cannot be said about the second force

which takes this particular form as a consequence of some additional assumptions concerning the form of the

’internal force’

. The first of the

two forces in (103) is the Lorentz force; it has been derived here (basically in the same manner as in the spinless

case) from first principles without any additional assumptions. The same cannot be said about the second force

which takes this particular form as a consequence of some additional assumptions concerning the form of the

’internal force’  [see (79)]. In particular, the field appearing in

[see (79)]. In particular, the field appearing in  was arbitrary as

well as the proportionality constant (g-factor of the electron) in front of it. It is well-known that

in a relativistic treatment the spin term appears automatically if the potentials are introduced.

Interestingly, this unity is not restricted to the relativistic regime but may as well be created in

non-relativistic treatments [4],[12]. A simple indication of this unity is the fact that the spin term

contains no new fundamental constants. One might speculate that an analogous formulation for the

present theory would automatically eliminate the above mentioned shortcoming. A most natural

framework to study this point - which is a subject of future research - is probably a relativistic

one.

was arbitrary as

well as the proportionality constant (g-factor of the electron) in front of it. It is well-known that

in a relativistic treatment the spin term appears automatically if the potentials are introduced.

Interestingly, this unity is not restricted to the relativistic regime but may as well be created in

non-relativistic treatments [4],[12]. A simple indication of this unity is the fact that the spin term

contains no new fundamental constants. One might speculate that an analogous formulation for the

present theory would automatically eliminate the above mentioned shortcoming. A most natural

framework to study this point - which is a subject of future research - is probably a relativistic

one.

In the present treatment spin has been introduced as a property of an ensemble and not of individual

particles. Of course, the properties of an ensemble cannot be thought of as being completely independent from

the properties of the particles it is made from. The question whether or not a property ’spin’ can be ascribed to

single particles is a subtle one. Formally, we could assign a probability of being in a state  (

( )

to a particle just as we assign a probability for being at a position

)

to a particle just as we assign a probability for being at a position  . The problem

is that, contrary to position, no classical meaning - and no classical measuring device - can be

associated with the discrete degree of freedom

. The problem

is that, contrary to position, no classical meaning - and no classical measuring device - can be

associated with the discrete degree of freedom  . Experimentally, the measurement of the ’spin of a

single electron’ is - in contrast to the measurement of its position - a notoriously difficult task. Such

experiments, and a number of other interesting questions related to spin, have been discussed by

Morrison [26].

. Experimentally, the measurement of the ’spin of a

single electron’ is - in contrast to the measurement of its position - a notoriously difficult task. Such

experiments, and a number of other interesting questions related to spin, have been discussed by

Morrison [26].